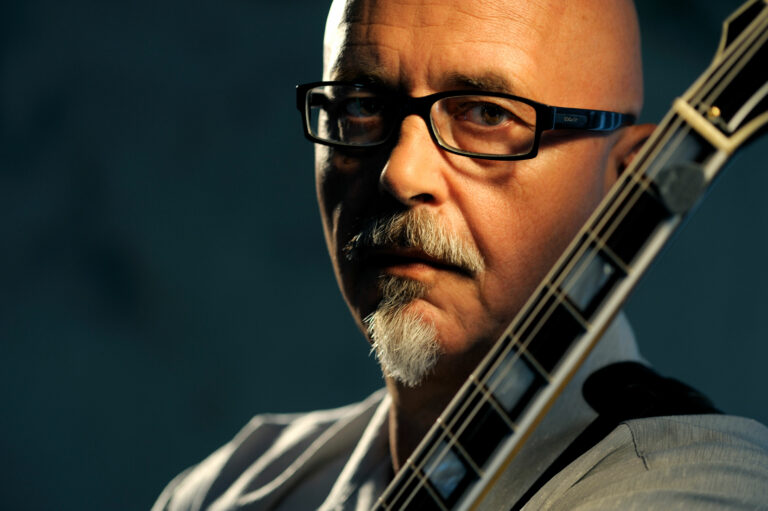

Prof. Dr. Tim Christian Kietzmann

It is said that there haven’t been any real universal scholars since Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz and his contemporary, Isaac Newton, or perhaps Alexander von Humboldt as well. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe could possibly also be added to the list: he was not only a writer and a politician, but someone who, at an old age, put his scientific work on the theory of colour even above his literary oeuvre.

Oh yes, he also discovered the human premaxilla. Besides these, in this category there are no longer any universal scholars. Nor does a certain Richard David Precht change this, for it is not enough just to claim that the title of universal wise guy for yourself.

But if there is anyone at all in modern science who comes at least close to being a universal scholar like those in times gone past, then they could really only be cognitive scientists. This is at least the impression you get when you talk to Tim Christian Kietzmann about his work. Firstly, he is a Full Professor for Machine Learning, and secondly, an internationally renowned scientist and figurehead for the Institute of Cognitive Science at the University of Osna-brück. But above all, he is a both enthusiastic and inspiring researcher who is passionate about his topic. When asked casually about his hobbies, he re-plies just as casually that he has turned his hobby into his career and therefore has no time for other hobbies beside his family. He gets just as passiona-te about what the brains of dolphins can do as about the finer points of self-driving cars.

It is precisely this huge bandwidth of modern cognitive science that permits a historical comparison with the universal scholars. Simply speaking, it involves interdisciplinary research into how information is perceived and processed, which eventually leads to decisions and actions, on the one hand, in the brains of people or animals, but on the other hand also in the software of computers or machines. Cognitive research is thus a key to understanding and developing artificial intelligence (AI) which is becoming ever more important in all parts of life, so that it also plays a leading role in the public perception of university research. At the same time, this also turns the leading figures such as Tim Christian Kietzmann into rockstars within the world of science, even if he’d never put it that way himself. But there are of course good reasons why, when he was still only in his early 40s, he was the one that Osnabrück Uni-versity chose toentice away from the well-known Donders Institute for Brain, Cognition and Behaviour at the University of Radboud in the Netherlands where his scientific career had taken him after working at the elite university of Cambridge in England and the Vanderbilt Vision Research Centre in Nashville, USA.

It must be said that for Kietzmann, who comes from Springe near Hanover, the call from Osnabrück actually also brought him back to his alma mater: “This is where I studied and did my doctorate, so I knew what a great university was waiting for me in Osnabrück.” After leaving school with an excellent “Abitur” (German school leaving certificate), he wavered between studying medicine in Göttingen (“My parents would have liked that”) and cognitive science in Osnabrück (“Scarcely anyone knew what that was in those days”). He decided in favour of Osnabrück. The young student was happy with his choice: “It was the first degree course in cognitive science in the whole of Germany, and it was just my thing.”

In promoting cognitive science, Osnabrück University backed the right horse right from the start. This is also one of the reasons why the Institute now has such an international appeal: “Here you find highly motivated, great students from all over the world who really want to study this subject at precisely this university.” His own team is international in composition and made up of brilliant minds from India, Switzerland, Ireland, China, Germany and the Netherlands. English is the only working language used for teaching and research.In promoting cognitive science, Osnabrück University backed the right horse right from the start. This is also one of the reasons why the Institute now has such an international appeal: “Here you find highly motivated, great students from all over the world who really want to study this subject at precisely this university.” His own team is international in composition and made up of brilliant minds from India, Switzerland, Ireland, China, Germany and the Netherlands. English is the only working language used for teaching and research.

Almost without taking a breath, Kietzmann starts enthusing about the human brain, the subject of his teaching and research: “A power station consisting of 86 billion cells that achieves such incredible things, while consuming just 18 watts in power, is actually an unbelievable miracle.” The young professor and his team are trying to fathom this wonderful brain and its wonderful functions, with state-of-the-art technology helping them to be increasingly successful. Corresponding research in the professor’s department at the university focuses on visual perception and information processing in people and machines. And although the scientists in Osnabrück can observe the brain with greater precision than ever before, now that it has been broken down into millimetre-sized cubes, so much of it still remains a mystery. This is what fundamental research is all about, says Kietzmann with a smile: “It can easily happen that we spend ages looking for something that just isn’t there.” A good portion of resilience is simply indispensable.

Although this kind of fundamental research doesn’t focus directly on specific applications, for example, in industrial production, there is almost always an indirect benefit: “That’s why we keep close to the manufacturers of agricultural machinery, for instance, who are strong employers in the Osnabrücker Land.” The name of his department, Machine Learning, says it all, according to Kietzmann. Modern harvesting machines, for example, are fitted with a large number of visual sensorsthat profit from the researchers’ findings about how people see and how their brains process what they have seen. Re-search from man to machine, so to speak. It also works the other way round, from machine to man, with the researchers using the latest, rapidly growing possibilities of AI for their brain research.

As with the old universal scholars, the cognitive scientists work on a very broad foundation. Besides computer scientists and mathematicians, neuro-scientists and biologists, the team also always includes psychologists, linguists and philosophers in teaching and research. They not only pursue re-search into whatever is feasible, but also think seriously about whether everything that is feasible really can and should be done – and if so, why and for whom. This social responsibility and this impact that science has on civil society is also something that Tim Christian Kietzmann feels is important: “We are not professors in an ivory tower: we want to be proactive in giving the community, whose taxes pay for our work, some feedback about what we’re doing here.” This is why leading researchers also devote their time to science communication, such as the “Brain Buzz” project initiated by Kietzmann, which gives hundreds of school children an opportunity to become familiar with cognitive science in the Botanical Gardens of Osnabrück University.

By the way, the father of two children thinks that the city of Osnabrück is an attractive place in its own right and not just as a university location: “When-ever I tell colleagues in our international research community about Germany in general and Osnabrück in particular, it’s always like a commercial break that extends from first-rate childcare to the good healthcare system and the safety and security of everyday life.” He draws a comparison to his time in Cambridge, where the childcare costs were so expensive that they more than consumed a second salary and it would have been cheaper for one of the parents to stay at home. For Kietzmann, Osnabrück is also an ideal size, as he can get almost everywhere he needs to go by bicycle, while still being able to use the comprehensive facilities and possibilities of a small city.

Finally, how about a suitable quotation, one that stays with the topic and shows what AI is already capable of doing? OK ChatGPT, find a suitable quota-tion from Goethe about artificial intelligence! Here is the answer, and it even comes with an interpretation:

“People only recognise themselves in people, only life teaches them what they are.“ (Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Faust I).

This quotation means that we only recognise our own true nature and our own identity by interacting with other people and through life itself. In the context of artificial intelligence, it could mean that machines or AI are also defined by their relationship to us humans, as we create them and give them their meaning. Many thanks, we could not have put it better.

Institute of Cognitive Science at Osnabrück University

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von Standard. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf den Button unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Mehr Informationen